REJUVENATE

Protecting, preserving and re-imagining our cultural and community assets for future generations.

The re-use of buildings is an integral part of creating sustainable architecture and vital in keeping the culture of our towns and cities alive.

We have been privileged to have had the opportunity to work on some fascinating historic structures. Buildings that have made their own history and influenced ours. Buildings that have given an identity to communities and played a pivotal role in bringing people together. Buildings that have seen many lives and have adapted to changing times. Buildings that have pushed technical boundaries and have advanced structural engineering. Some buildings that only just remain standing, and no one really knows how!

Rethinking buildings for future use creates challenges and opportunities. Combining low carbon, heritage-led regeneration with conservation we can reveal and preserve the past whilst bringing new, contemporary, accessible lives to these spaces.

Our cultural heritage represents an important echo of our past but is also a vital part of our emerging, sustainable future.

WORKING WITHIN CONSTRAINTS AND RESPONDING TO OPPORTUNITIES

What is it that makes buildings respected, if not treasured and admired? Historic England define significant buildings in terms of their cultural, technical, architectural and historic attributes. But there is often a more subjective response, based on our own appreciation or the role of a building in its community, that guides our approach and decision making. Together, these lead us to appreciate the strengths and weaknesses of what we have to work with and help determine the architectural outcome. At Alexandra Palace theatre, when faced with a building that had not been used for decades, we chose to capture the intriguing sense of ‘arrested decay’, rather than restoring or replacing the interior as it was originally conceived. At London’s Southbank Centre we strongly believed in the power of the Brutalist architecture. We were the only practice in a strong international competition who felt we should ‘retain and enhance’ what was there rather than demolish and rebuild. A few key moves symbolised this approach. One example was the redefinition of the Hayward Gallery’s rooflights which were not part of the original design but appeared as a response to Henry Moore’s statement that the ‘Light of God’ should be admitted to the top galleries. The tall pyramidal structures never worked - they leaked and let in too much sunlight- but they had become an iconic symbol of the building. We reconfigured them to simplify the glazing as a near-horizontal frame with a pyramidal steel and white glass structure floating above to provide solar shading, fulfilling their functional and aesthetic presence.

Alexandra Palace, London

Southbank Centre, London

BUILDINGS THAT HAVE CHANGED

THE COURSE OF ENGINEERING

AND ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY

Some of the greatest historic buildings that we have and continue to work on are ones on which the original designers took risks and pushed boundaries. Forensically unpicking the history of architectural development and understanding the socio-economic as well as technical constraints adds an extra dimension to our design task. Two interrelated projects for the same family of industrialists, 40 years apart, exemplify this approach. The Shrewsbury Flaxmill was the first building to use a cast iron frame, and as such could be seen as the ‘grandparent’ of every skyscraper in the world. Developing a new material technology inevitably led to unknown risks and the building was near to collapse when we were brought on board by Historic England. With engineers AKT, we provided a strongly reinforced structural base that allowed us to tie the upper three floors of the building together with the simplest of tie rods. This proved a strategy that had the least aesthetic, and embodied carbon impact. The next generation of the same family looked to push boundaries in a different way. When Temple Works in Leeds was developed it was the benefits of maximizing daylighting and therefore the working hours of an exploited workforce that drove the design. This lead to the first building that we know of where the daylighting was modelled and measured, but also to the construction of a building which for a long time held the record for the largest enclosed footprint in the world. These buildings were essentially designed by engineers, with the buildings becoming an extension of the machinery they housed. Our job now, as architects, is to continue to push boundaries in order to reuse, rejuvenate and recreate these buildings to serve our contemporary communities.

Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings

Temple Works, Leeds

DESIGNING FOR

SECOND LIFE

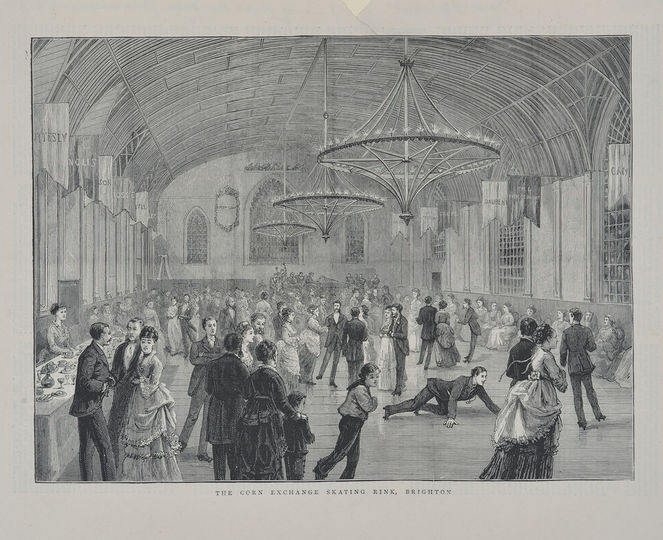

Many buildings have been through a number of reincarnations and adapted themselves to new uses. They often have hidden histories and layers of decay and refurbishment. The Corn Exchange in Brighton has had many lives going from a very private wealthy riding stables to a public arts venue. In providing a new life for it, the most valuable contribution we could make was to restore and strengthen its amazing single span timber roof and reline it with the timber boarding it had during its first incarnation. Everything else we did was simply designed to generate as much flexibility for future uses. We added air conditioning, retractable seating and staging, a lighting rig, understage storage and a new front of house with bars and cafes. Careful design of all these ancillary facilities has given a new dignity to the magnificent central space, as it enters this next phase of its life. In a similar vein, but 30 years earlier, when we were asked by Peter Gabriel to create a new recording studio in a redundant agricultural water mill, we stripped it back to the bare structural carcass of stone and timber and gave it a new life with a new language. The interior architecture was derived from the necessities of air conditioning ductwork - using fired clay drainage pipes to deliver the air - and acoustical glazing and diffusers for sound absorption. And so, a new functional language emerged based on sound, light and air, and a new era was begun.

Brighton Dome Corn Exchange

Real World Studios, Box

WORKING TO REDUCE

CARBON EMISSIONS

Taking climate change seriously means that much of the new build work we are asked to develop is an unacceptable extravagance. Not so much because of the ongoing operational energy that buildings use, but because of the embodied carbon costs of construction. Since the bulk of this is in foundations, frame and external envelope, retaining these from an existing building saves the bulk of new build carbon costs, and upgrading the energy performance during renovation cuts future operational carbon emissions. At the Cultural Heart of Kirlees in Huddersfield we are retaining and upgrading two listed buildings but demoloshing other low-grade buildings around them in order to create a new urban park in the centre of the town. The new scheme will see the dramatic revelation and transformation of a 1970's concrete market structure, enhance and thermally upgraded. But by retaining the basement parking and service spaces, we hope to recycle both the concrete from the frame and the stone cladding of the unwanted buildings we are demoloshing, generating a circular economy in building materials that is necessary for the construction industry in order to improve its reputation for generating more than 25% of all the waste in the country. In the recent restoration project at Bath Abbey our work is largely invisible. But by removing the Victorian pews we have created flexibility in the use of the space and provided much more comfortable seating. And in revealing and repairing the subsidence of the floor we have also installed an underfloor heating system powered by the waste water from the geothermal springs of the Roman Baths nearby. We also saved huge energy costs in the process of relighting and revealing the stone vaulted ceiling above.

Kirklees Cultural Heart

Bath Abbey

BRIGHTON DOME : 8 LIVES OF AN EXTROADINARY BUILDING 1803-2023

The grade II listed Brighton Dome Corn Exchange has had many guises since in was built for the Prince Regent in the early 19th Century. From a Victorian skating rink to a military hospital and then as a venue for an array of illustrious artists, writers, musicians, and actors. The changing role it has played has been pivotal to establishing its identity within the city, both as a leading arts venue, but also as heritage asset for the local community.

Now open to the public once again, a new chapter begins providing a truly dynamic cultural offer for the city and the region. One which responds to what has gone before but creates new opportunities for the future.

The re-use of buildings is an integral part of creating sustainable architecture and vital in keeping the culture of our built environment alive. We combine specialist low carbon heritage-led regeneration with conservation as part of managing change, bringing an innovative approach to existing buildings and historic contexts

See more of our creative re-use projects on the FCBStudios website.